Salem today rates about a seven on the dreary scale— not much to see, despite its touristy cant. But up until about sixty years ago, Salem boasted the most spine-tingling eerie Gothic-Norman stone train station in North America.

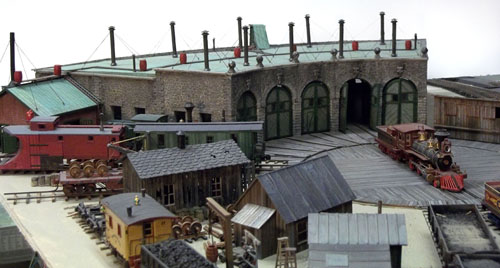

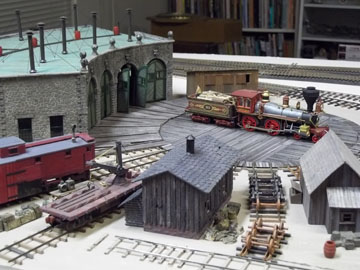

For all its Frankensteinian grandeur, the station was a mere two-track covered trainshed, a product of the 1840s, with a nearby coach yard and roundhouse and a small public square out front. Perfect for modest-sized modeling. I chose this to be my layout's centerpiece.

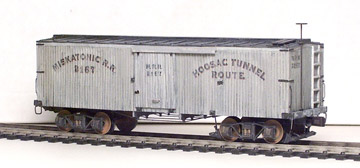

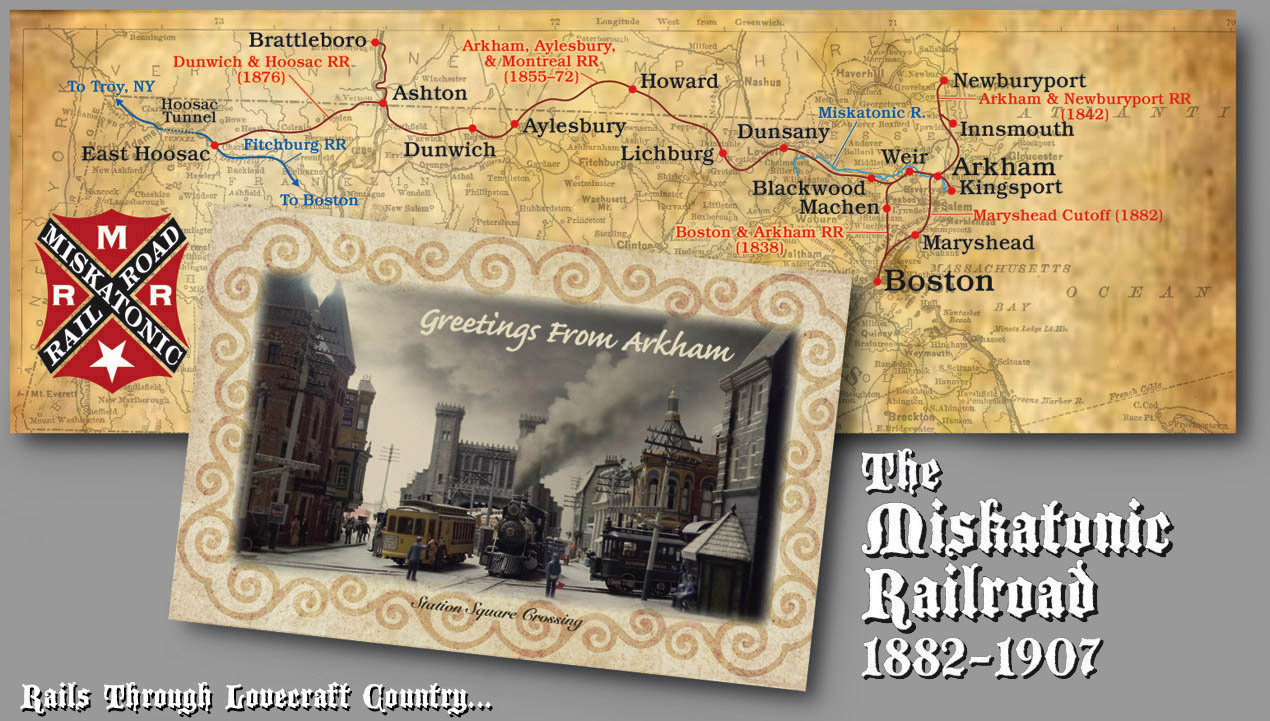

Salem was served by the Boston & Maine RR. (Originally, the Eastern RR.) In my version of events, Arkham is a main junction point between the Boston & Arkham RR and the Miskatonic RR, which I imagine to be a feeder line for the western Massachusetts Hoosac Tunnel route, linking the mill towns of northeast Massachusetts to upstate New York and points west. The Miskatonic also connects with lines to Newburyport (and points north), and Kingsport (another town from the Lovecraft mythos.)

For a short history of the Miskatonic Railroad (at least, according to some), click here.

Left middle: Another shot of the station, this time c. 1900, with an old 4-4-0 smudging up the facade. Scenes like this inspired my own vision of Arkham.

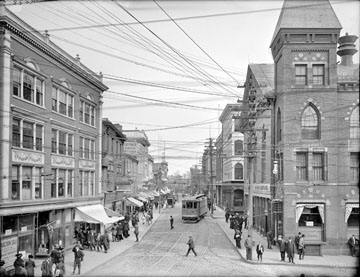

Left bottom: Cobblestone-paved Essex Street, just up the block from the station, was typically narrow and like many things in northeast Massachusetts, slightly twisted.

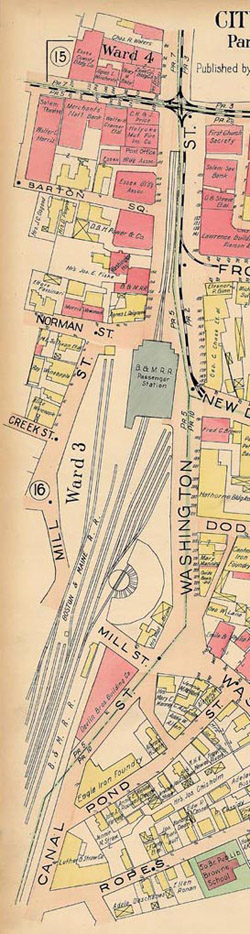

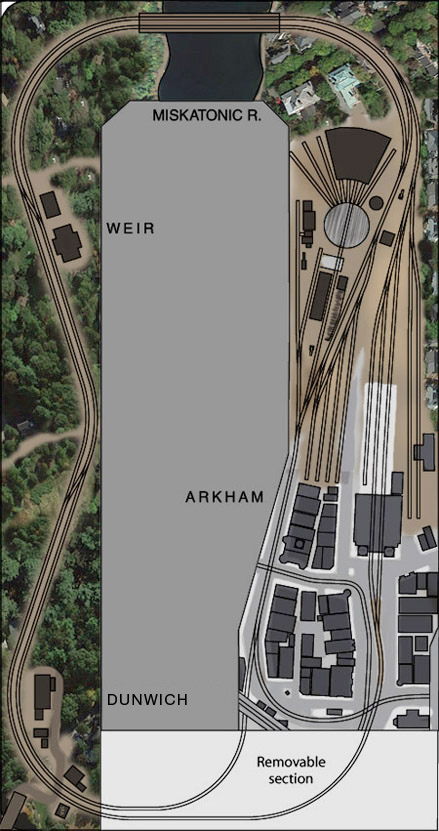

Below: Lovecraft scholars have made maps of Arkham based upon H.P.L.'s notes, giving us street names and locations for civic landmarks like the famed Miskatonic University and the train station. I incorporated these street names into my layout plan.

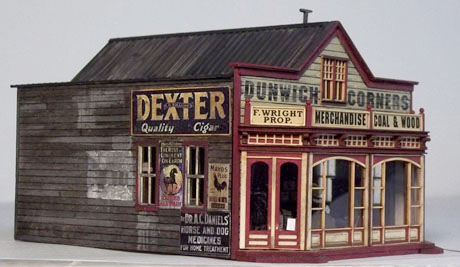

Other names on the layout come from 19th-century fantasy fiction— like Dunsany, Blackwood, or Howard— or names from Lovecraft and Poe— Dunwich, Innsmouth, Aylesbury, and Weir.

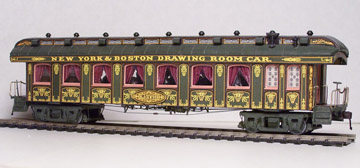

OPEN-PLATFORM PASSENGER CARS

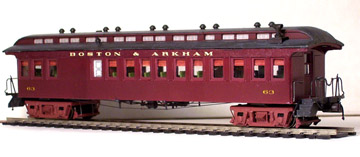

The main business of the Miskatonic Railroad is hauling passengers from one dreary industrial age burg to another. Trains run several times a day between Arkham and Boston, and there are daily trains that travel west through the Hoosac Tunnel to Albany, New York and north to Brattleboro, Vermont to connect with the lines coming south from Montreal.

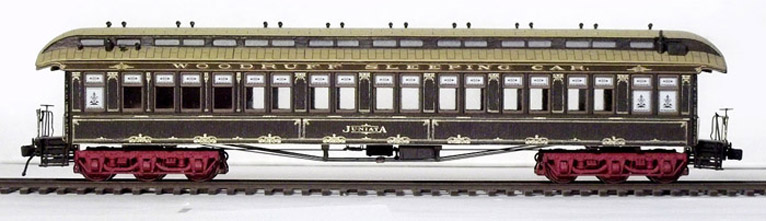

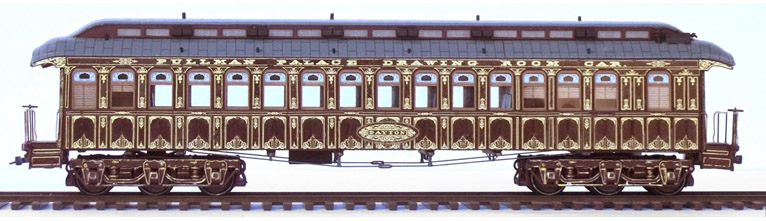

Until the dreaded Eastlake style simplified everything in the late 1880s-1890s, passenger cars were ostentatiously decorated with gilt, paint, carving, and marquetry in order to show off the host railroad's financial well-being, attract patrons with superficial luxury and finally, to distract them from the very real discomforts of late 19th century train travel.

Decorative passenger car decals for HO are notoriously rare. I took the opportunity to make some of my own, using Adobe Illustrator, a good laser printer, and some stock decal paper.

Sharing decal art brought me into contact with master modeler Håkan Nilsson at Eightwheelermodels.com. I had a delightful opportunity this year to contribute artwork for his first two 3D printed kits— the Dayton, an 1871 Pullman, and the Juniata, an 1880s Woodruff sleeping car (upper right). Håkan's craftsmanship is superlative and the two cars have to be the most accurate HO models of 19th-century passenger cars ever produced.

Most of the others are 50-foot cars, short but fairly common on 1880s-1890s Eastern roads. Some are modifications of kit-built cars, some use custom resin castings, and some are scratchbuilt with the addition of parts from Grandt Line, Bitter Creek, Cal-Scale, and others. All have metal wheels, trucks with outside brake beams, soldered platform railings and scale-sized Accurail couplers which sort of look like the Miller hooks of the prototypes.

I love Silver Crash resin cars!

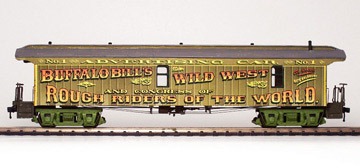

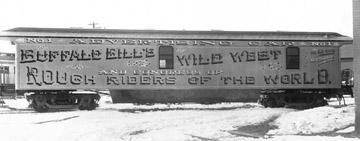

Traveling shows were an important part of late 19th century–early 20th century American life. By far the most renowned traveling show was Buffalo Bill's Wild West and Congress of Rough Riders.

Shows like Buffalo Bill's sent advance teams ahead in their own colorful advertising cars. These cars would be attached to the rear of normal passenger trains and parked on a siding somewhere near the depot. Weeks before the arrival of the show, the "drummers" papered a town with posters, sold tickets, and in general "drummed up" excitement.

I found some good pictures of some of Buffalo Bill's advertising cars on the internet. For making home-made decals and print-sided cars, these proved to be an irresistable challenge.

Master modeler Don Ball made a set of these cars back in the 1980s and wrote about the experience in Railroad Model Craftsman. His article was an inspiration to me. Later on, I had the happy opportunity to return the favor by sharing my new decal art with Don.

Cars #1 and #2 have scratchbuild bodies and platforms. Car #2 has a shortened MDC/Roundhouse duckbill roof and Bitter Creek trucks. Car #3 is a mostly stock MDC/Roundhouse overland car. Lucky me— it had just the right number of windows.

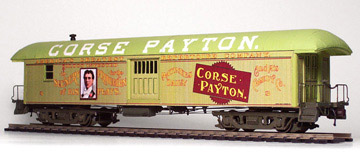

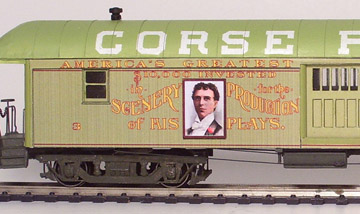

Lastly, at the bottom of the column, is one more traveling show car. In the 1890s, Corse Payton's repertoire companies rode the rails bringing stage plays ("A New Show Each Night!") to small-town America. In an era before 3D movies, HBO, Netflix, and Hulu, this was a very big deal. Townspeople turned out in droves to see fantastic sets, gorgeous costumes, and hammy acting by young performers, some of whom went on to become famous silent movie stars.

Payton's investment in sets and scenery grew so great that he had his own car made to transport it all. I found pictures of it on the Delaware Public Archives website.

The body of the model and the platforms are scratchbuild with printed overlays. The roof is from a MDC/Roundhouse Harriman coach. The trucks are from Bethlehem Car Works.

Layout construction began in early 2013 and is proceeding at a leisurely pace— much like the prototype railroads of the period. Tracklaying advances whenever there are opportune infusions of capital— kickback-fueled congressional subsidies, tissue-paper bonds, stock swindles, or whatever.

Like my previous San Diego layout, this one is built atop layers of foam-core and insulation foam. Since I'm re-using my San Diego layout's wood components, the layout is high— about 50". My workbench is underneath. The "U" fills a space 16' x 8'.

I'm hand-laying some code 55 track to represent the light iron of the 19th century. I'm also building many of my own switches, some stub, some point. Rails are soldered to PC-board ties from Clover House. Klapper supplies the wood ties.

Main-line tracks and most trackage far away from the edges of the layout will be code 70 flex-track and switches from Micro Engineering. (Wish they still made code 55 flex-track!)

I consulted old railway engineering texts to figure out what the tie spacing should be to represent late 19th-century track. I went with 2' spacing for main lines, 3' spacing for secondary and yard tracks, and 4' for dead end sidings and yard tracks. You often see worse in old pictures.

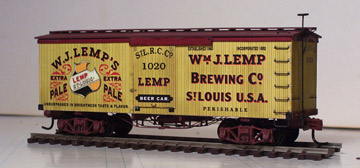

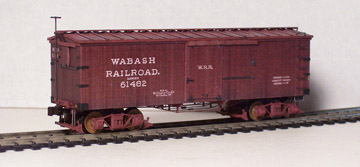

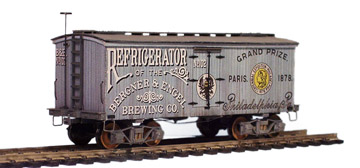

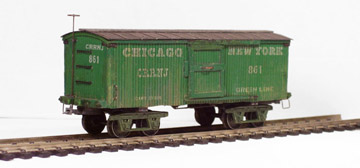

The backbone of the Miskatonic freight car fleet continues to be limited-run resin-cast creations, either by Silver Crash Car Works or the team of John Canfield and Bob McGlone (top picture, right). The layout also has a large collection of period cars with printed sides.

Long ago, in an age when dinosaurs (like me) ruled the earth . . . there was such a thing as print-sided HO freight cars, made by Ulrich and other kit manufacturers. These car sides were printed on cardstock complete with road names, reporting marks, etc. Since this all happened in an age before Photoshop, the sides noticably lacked realism. Scribed wood or plastic plus decals gave far better results.

I decided to give printed sides another try— on my own, armed with Adobe Photoshop, Adobe Illustrator, and a good color laserprinter. This time out, the lettering, wood texture, grooving, and weathering were painted in Illustrator and Photoshop. The rest of the car was built conventionally: with a plastic or crescent board car-box; Bitter Creek, Rio Grande, or Tichy trucks; Accurail couplers; and lots of add-on details from Grandt Line or Tichy (middle, right).

At the time, it seemed to be the best way to build a fleet of accurate 1880s-1890s cars quickly and economically. How quick? Click here or on the annual report banner below— "Eight Cars in Eight Days."

It is my intention to have locomotives dating from each decade of the last half of the 19th century— tiny 4-4-0 teapots from the 1850s and 60s (like the ones at right), medium sized wagon-top-boilered 4-4-0s from the 1870s and early 80s, and finally, bigger black-painted 4-4-0s and 4-6-0s of the 1890s and beyond. Freight engines will be represented by 2-6-0s and 2-8-0s.

Engines back then were gleaming Victorian jewels of paint, gilt, brass, copper, Russia Iron, and polished steel. Wooden cabs were crafted as fine as furniture. No two locomotives were alike and most had names instead of numbers. Their crews were proud of their machines and polished them daily.

... Won't win any civic beauty awards. The model is supposed to represent one of those smoky, dirty, busy American east coast cities at the turn of the twentieth century.

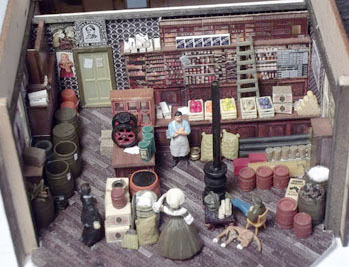

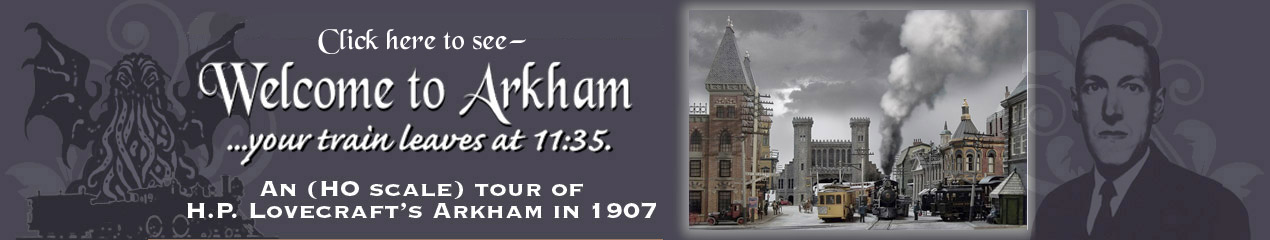

Arkham is a combination of scratchbuilt, kitbashed, and straight kit buildings. Several have been salvaged from my previous layouts. All of Arkham's streets are kinky—they all have twists and bends, which means the blocks are irregular and the building lots are largely trapezoids— just as in real-life Massachusetts. The feature "Welcome to Arkham" tells more about building the model.

The name "Miskatonic" comes from the iconic horror stories of H.P. Lovecraft. The choice of name reflected my discontent at being exiled from my sunny homeland of Southern California to the history-haunted cityscapes of Boston, Massachusetts. For four long cold years I lived in a cramped apartment a short driving distance from the heart of "Lovecraft Country"— the northeast portion of the Shadow State that was featured in Lovecraft's eldrich tales of the horrible Great Old Ones and what happened to them when they met Massachusettians. (Hint: they got grumpy; justifiably so.)

Back in sunny Southern California, I turned the Miskatonic into a real layout. At left is the ever-evolving track plan. It's a basic "U", with medium curves and a temporary drop-leaf loop for the occasional continuous running of trains.

Outside the main station stop in the city of Arkham, I've planned a river crossing, small towns, abandoned mills, and dense, haunted woods.

One thing I'm going to really be paying attention to is lighting: trains and buildings will all be illuminated. I'm thinking about a projector lamp to shine a rising moon on the wall. I want this railroad to be able to be run at night.

My version of Arkham city started as a few square feet at one end of the layout— and like the Outer God Azathoth, seemed to grow exponentially, until it became the layout's focal point. It's the first part of the project to reach a point where I can call it "finished"— for now. My first victory over creeping Primal Chaos.

The roundhouse was built of 1/4" foam-core covered with Plastruct textured styrene, same as the depot below. The covered turntable is an old Atlas product with a new layer of planks. Turntables in new England were often covered because shoveling the snow out of a turntable pit was as hellish a job as any imaginable.